In Good Taste #2: Sauerkraut

Starting with sauerkraut and what it can teach us - a lacto-fermenting 101; finding relief from monoculture; a nature book recommendation

Well, hello there! How are you?

Good I hope. Thank you so much for being here.

When I started writing the first draft of this email (Tuesday) I was feeling very Fotherington Thomas. Very “Hullo clouds, hullo sky”. Because spring had definitely, incontrovertibly sprung. And not that fake spring that happens in early March when the first daffodils come out and you get all excited but then it hails on you and is grey and cold for another month. No. Actual, real spring.

Today (Thursday) things look a bit drizzlier but my mood remains relatively buoyant. I'm not at home but this was the tree outside my house yesterday. There were so many bees enjoying the blossom that it was giving off an audible hum.

This time of year is also one of my favourites to start fermenting things. The cold of winter can make things a bit sluggish to get going but summer can sometimes be too fast-fizz for my liking. But stuff happens at a good rate in spring.

So, did you make some pink pickled turnips last week? If so, how are they doing? They might not be quite ready yet but should be well on their way. Any questions let me know in the comments or drop me a line.

I promised we’d return to sauerkraut and now seems a good time to do it.

Apologies in advance for the lack of good photos in today’s newsletter. As I said, I’m not at home at the moment. We’ve let out house out on AirBnB so are staying at my brother’s place in Cambridge on cat-feeding duty. I thought I had more kraut-illustrative pictures on my phone but I was wrong. Instead here is a picture of Sammy, the cat in question, choosing this moment to become sociable.

Anyway. Sauerkraut is usually most people’s gateway into lacto-fermenting and with good reason: it’s super simple but also delicious and versatile. It’s usually the thing I start with on my courses as it’s a great way to lean into the basic science of what’s going on.

The word literally means “sour cabbage”. The cabbage is sour because it has been fermented with lactic acid bacteria. This is fundamentally what makes a lacto-fermented pickle different from a vinegar pickle. To make a vinegar pickle we pour vinegar (probably along with some sugar, salt and spices) onto our produce. Job done. For a lacto-fermented pickle we create the right environment for the lactic acid bacteria (lactobacillus) to thrive. They convert sugar into lactic acid. The lactic acid pickles the produce. So it’s an ongoing process, a working partnership with the friendly bacteria.

So. How do we create the conditions for our bacteria pals to do their best work? I’ll tell you.

Lactofermentation 101

There are microorganisms - bacteria and yeasts - all over the place. In the air, on fruits and vegetables, on our skin etc. These include the lactobacilli that we want to collaborate with but also all sorts of “bad” bacteria too - the type that make things decay and mould. If we just took a cabbage and left it on the table, eventually it would begin to rot. But if we create an environment which is inhospitable to the bad bacteria but in which our lactobacilli are happy then they will create our pickles for us.

There are 2 things we need to consider here:

Salt

Oxygen

Salt inhibits the growth of most of the “bad” bacteria so but lactic acid bacteria are fine with it. So first we add salt. How much salt? I like to use between 2% and 5% of the weight of the vegetables. Less than 2% might not be salty enough to keep the bad bacteria at bay, more than 5% is inedible except in very small quantities. I generally use 2.5%.

Secondly, oxygen. Lactic acid bacteria are anaerobic, meaning they don’t need oxygen to survive. The bad bacteria do.

So creating a salty, oxygen-free environment means our lactic acid bacteria are happy and the bad bacteria can’t survive. There are two ways of achieving this. Last week, with our pink pickled turnips, we made a brine and poured it over the vegetable chunks. This time, we’re using dry salt to draw out the moisture in the vegetable itself. This dissolves the salt and creates a brine. Then, weighing down the vegetables so they stay under the brine and sealing the jar well minimises the oxygen they come into contact with.

This is the fundamental principle you must remember to make lacto-fermented pickles: Under the brine, everything’s fine.

So, shall we make some sauerkraut?

Recipe: Sauerkraut

You’ll need a large jar or fermenting crock. If you want to sterilise it you can do this by running it through a quick hot cycle in the dishwasher, boiling it for a few minutes in a pan of water or putting it in a 100°C oven for 20 minutes. But you don’t need to. Cleanliness is much more important than sterility since we’re creating an environment that is inhospitable to “bad” microbes anyway.

These quantities make roughly a 750ml/1l jar depending on the size of your cabbage but feel free to scale up or down.

Ingredients

1 head white cabbage

sea salt

caraway seeds (optional)

Method

Cut the cabbage into quarters lengthwise and cut out the hard cores. Don’t throw them away though - we’ll use them as pickle weights later.

Put a large bowl on a scale and set it to zero. Then finely shred each cabbage quarter, adding it to the bowl as you go. If you have a mandoline it can come in useful here. If not then a sharp knife and some patience is fine.

Take note of the weight of the cabbage (it will probably be between 800-1200g). Calculate 2.5% of that weight and add this in sea salt, e.g. if the cabbage weighs 1kg (1000g) then you need 25g salt.

Add the salt to the cabbage and toss well. After just a few seconds you’ll notice the shreds of cabbage begin to feel damp as the salt draws out water. Leave for between 30 minutes and overnight, depending on your schedule.

Once the cabbage has sat for a while there should be a small puddle of brine at the bottom of the bowl. You don’t need loads but there should be at least two tablespoons-worth - if things are looking a bit dry, give the cabbage a good massage until you have a little more brine.

Add approximately 1tbsp caraway seeds (if using) and toss to distribute them evenly.

Put the cabbage in the jar and add the brine. There should be enough brine so that when you push down firmly on the cabbage, brine rises up around it and covers it. Use a glass or ceramic pickle weight, a plastic bag filled with water or the cabbage cores you saved from earlier to keep the cabbage pushed under the brine. Ideally when you shut the lid it will keep this weight in contact with the cabbage.

Put the jar somewhere at room temperature but out of direct sunlight and leave it. Every few days open it up to let out any gas that has collected and to taste a little kraut. When the kraut has reached your preferred degree of tartness, move to the fridge. This will probably take between one and three weeks.

Notes

The caraway is a very traditional partner for cabbage, both cooked and fermented, but is totally optional. I’ve included a few other suggestions below. But this basic method covers a world of possibilities and I hope you’ll experiment.

Sauerkraut will keep in the fridge for months and tends to stay crunchy for a long time. If you prefer a softer texture massage the cabbage really well before putting it in the jar.

If Ifs And Ands Were Pots And Pans

These are a few of my favourite kraut variations. All will work well with 2.5% salt.

Fermented slaw: combine your shredded cabbage with grated carrot and thinly sliced onions.

Curtido, a central American version includes cabbage, carrot and onion as above but also oregano and jalapenos. It’s great in tacos.

Red kraut: use a red cabbage instead of white and include a couple of teaspoons of the sweet spices you’d use if you were braising it, e.g. cinnamon, star anise, crushed juniper berries. A grated apple and/or beetroot is a good addition too. Alternatively red cabbage and beetroot flavoured with crushed garlic and grated horseradish is a delicious accompaniment to cold meats.

Carrot kraut: at least two days a week my lunch is hummus on toast topped with some form of carrot kraut. I’ve always got a jar in the fridge, usually made with garlic, chopped herbs (dill and tarragon are current favourites although if you have carrots with nice bushy green tops then these work well too and have a lovely fresh, grassy flavour) and whatever seeds are in the cupboard. Sunflower, pumpkin, sesame and poppy all work well separately or together.

Cultural Fun

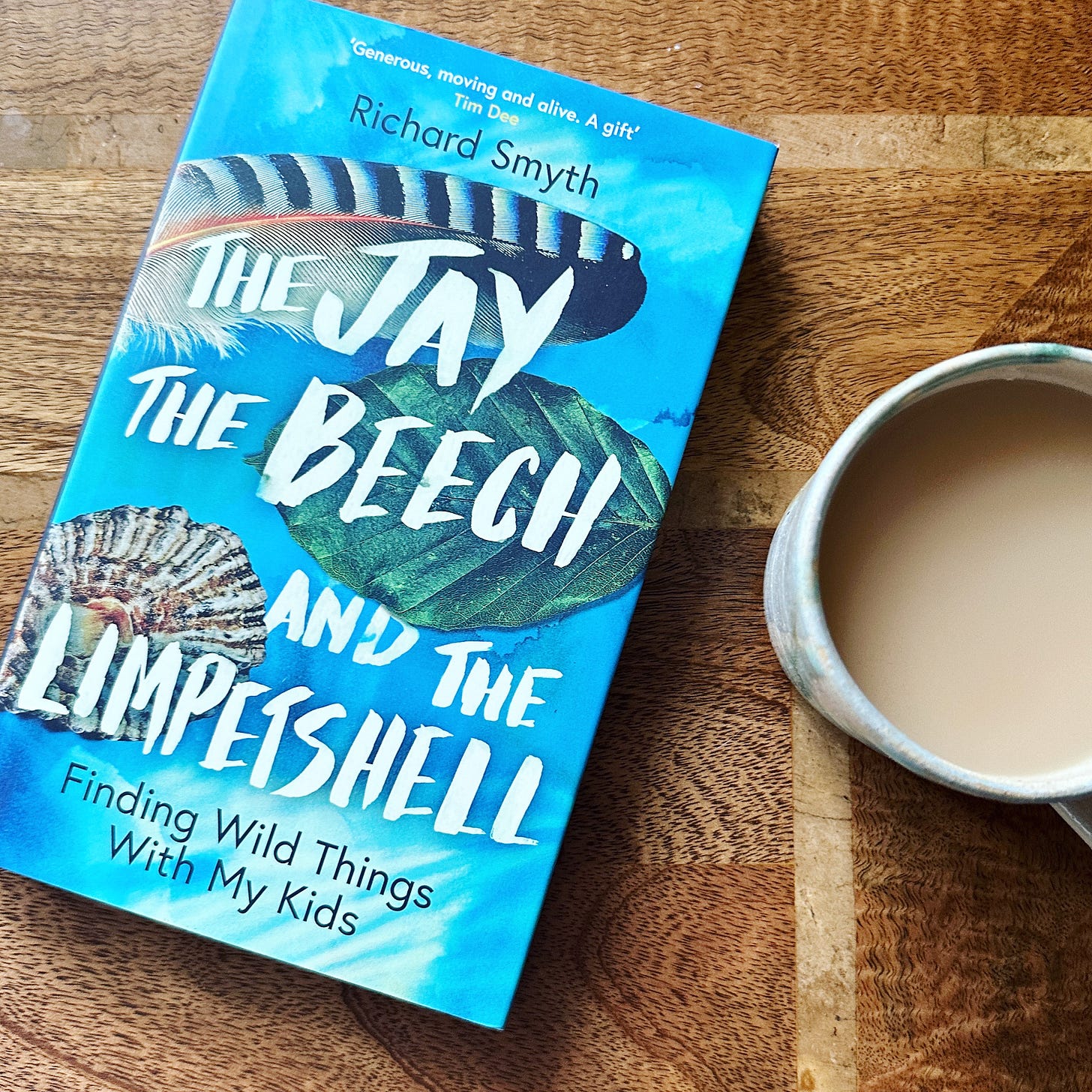

My brother-in-law, Richard Smyth, has a new book out. Obviously I wouldn’t tell you about it if I didn’t think it was good but thankfully (for the sake of a non-awkward Easter lunch) I do. The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell is about exploring nature with children. It’s a sort of history of natural history mixed with memoir and environmentalism. An interestingly new kind of nature writing. Funny too.

I read this article about why everything is the same and it really struck a chord.

I’ve been fixated on this idea for a while now. Murrell references architecture, interiors, products design and even faces. I hadn’t clocked these things in quite the way he articulates but for the last few years I’ve been creepingly aware that, sicne so much of life is lived online, we see the world increasingly through portals - and therefore aesthetics - that we didn’t choose.

I mean, look at this newsletter for example. I can include pictures and links but beyond uploading a logo and a rudimentary choice of fonts, I get little input in how it looks to you - what vibe you get from me. It’s mostly clean white space. Like most websites these days. Clean white space, san serif fonts and bright or pastel colours. Which has got to affect your impression of the world, right? And your impression of me (if you came to my house you’d see it is very much not full of clean white space). To me this way of experiencing things feels flat. Literally and metaphorically. And I think it’s why I’m increasingly obsessed with texture.

I used to like clothes that were plain and monochrome. I thought they were smart and minimalist. Now the whole world (as experienced through my smart phone or desk top) feels so one-note, I’m desperate for unevenness. I haven’t reverted to the tie-dyed crushed velvet of my teens but I can see the appeal…

I’m a member at a pottery studio and I love how each piece comes out if the kiln with its own variations in glaze (even if I don’t like the drips on my most recent mug). Perhaps it’s another thing I like about wild fermentation: you can’t completely control all the variables so things inevitably play out a little differently each time. At the very least, it’s not average.

Since we’re coming up for Easter, I will share my annual tradition of reading David Sedaris’s story Jesus Shaves. You can hear him reading it on an old episode of This American Life or read a shorter version here with your own eyes. It makes me laugh every time.

Last week I recommended Ben Moor for enthusiasts of weird comedy. But I guess he’s more whimsical oddball. If you like really weird comedy then try Kim Noble. His show Lullaby for Scavengers is at the Soho Theatre until Saturday. It’s a difficult watch in places but I really enjoyed it.

Bye! See you next week!

In the meantime, if you felt like sharing In Good Taste with friends or family who might enjoy it, you can do so with the button below. It would mean the world to me. Thanks so much.

In Good Taste is a Sycamore Smyth newsletter by me, Clare Heal.

You can also find me on Instagram or visit my website to find information about my catering work, cookery lessons and upcoming events.